"The closest to perfection a person ever comes is when he fills out a job application form." - Stanley J. Randall

A true story; with GONZO Enhancement

The theme of the History Channel's "Modern Marvels" program this morning was "Inviting Disaster". The program featured Three Mile Island.

I was in college in 1979, at Park College in Pittsburgh, when the genie of nuclear disaster first escaped the bottle. I dragged into my 9 o'clock copy writing and editing class with a wicked hangover.

The professor - Journalism Department Chairman Vincent LaBrasca - sat quietly behind his desk; waiting for the lingering few who would invariably arrive late. Coming to Professor LaBrasca's class late was always a gamble; at best you would get "the look"; at worst he would stop the class. The one thing you never knew was what he would have to say. Having him sit there as the minutes ticked by, seeming like hours, was the first sign this was not going to be a typical morning.

Normally he would be chatting and laughing as we arrived. He managed the class in such a way that it didn't take long to know what to expect. The standard procedure was that he would begin precisely at the top of the hour. After writing the day's subject topic on the chalk board, there would be a short introductory lectuture followed by lively discussion through the remainder of the session.

This morning, as he sat and waited, the room was quiet. Bright sunshine streamed in, warming my back as I sat in the last row. But it didn't do anything for my pounding head or my stomach turning and twisting. Why hadn't I stayed in bed, I thought. Just then, the blood vessels constricted; I winced as it felt like a dagger was being thrust into my skull. I thought my head would explode at any moment. Things would only get worse.

The professor continued to sit, and wait, silently. The clock on the wall showed seven minutes after the hour by the time the fifth person arrived late. "Do you think anyone else will be joining us," he asked; in a gravelly voice that came from a lifetime of smoking sitting at a manual typewriter banging out the news of the day. He got up, slowly walked around and sat on the front edge of the desk. Leaning back, he asked, "Who can tell me...what happened last night?"

I'd had a long night shooting pinball at Smithfield News and drinking pitchers of Iron City beer at Jimmy's Post Tavern into the early hours of the morning. Then returning to the dorm, rolling a few fat joints of sweet sensimillia and laughing our assess off reading The Fine Doctor's FEAR & LOATHING IN LAS VEGAS.

Normally, I actively participated in the class discussions; frequently turning them into debates. My head throbbed this morning, though. I could barely assemble a clear thought let alone participate in any debate. The only saving grace was that no one knew what had happened overnight in Middletown, Pennsylvania; nor what was continuing to unfold that morning.

Just then, another person walked in. "Good morning," he said, turning toward her and flashing a wide smile. "Thank you for joining us. Were you watching the news?" Told no, he shook his head. "What in God's name are you people DOING HERE," he roared spewing disgust and disdain. "How are you going to write news when you don't know what's happening in the world? You don't know what is happening in what may as well be your back yard!!"

Something happened overnight, he told us, that could have a profound impact on our future. The eruption of Mount LaBrasca continued, "You don't know how lucky we all were to wake up this morning." That was it. He got up, walked back around the desk, put his suit coat on and went to the door; shaking his head with each step. Before walking out, he looked back and said, "Go and find out what the hell's going on!!!" The door SLAMMED behind him.

Like crack addicts looking for our next fix we were off to the races! The resources that exist today, the access to information, the speed at which you are able to respond to a situation were not available in the late 70's.

There is one thing that has not changed. Government response then, as it is all too commonly now, was to say what people wanted to hear regardless of the truth; to deny; to minimize; to stonewall; to misrepresent; and worst of all to speak as though they had accurate information when they didn't know what the hell they were talking about.

I did all I could to learn about nuclear energy, to try and understand the things that were happening and the things that could happen at Three Mile Island. It was made more difficult by the smokescreen the State of Pennsylvania and the Nuclear Regulatory Commission were putting up.

We returned to class two days later. "What have you people done since we last met," Professor LaBrasca asked. He went one-by-one. Some had drafted articles, some had folders of research; some said they had been watching television to keep up-to-date with what was going on." Watching television was not what he wanted to hear; although the rest of us did not fare much better.

Professor LaBrasca had spent a lifetime working in the newspaper field. He'd started as a copyboy and built a career to work as the Managing Editor at one of the most prestigious newspapers in the country. I had written for a weekly newspaper for almost three years before entering college. I got one raise during that time; from 15 to 25 cents per column inch published. I wasn't doing it for the money. I loved newspapers. I had the good fortune of meeting Professor LaBrasca when I began looking at attending college. It was something I never thought of. I was going to school, working at the paper, focusing on developing my writing skills. My editor had studied under the professor. If I wanted a career as a newspaper reporter, she told me, I would need a college degree. She arranged a meeting and we went to Pittsburgh to visit the school. I enjoyed my meeting with Professor LaBrasca. His enthusiasm for journalism was palatable. After the meeting, as I went through the application process, Professor LaBrasca showed interest in my career. He went as far as having me send articles for his critique during my senior year in high school.

The professor had each of us come to his desk with whatever work we had done since the last class session. I handed him the feature article I'd drafted. He looked at me with steely eyes. "You're BETTER THAN THIS," he said. Once everyone was seated, the professor begin to lecture; pacing back and forth across the room.

He spoke of his trip the previous summer to Russia; where there was no free press. He told us how his group was only allowed to travel on trains at night; enabling the Russins to control what they would see. He spoke of the responsibilities you take on if you choose to report the news. He talked about what happens, what can happen, when the press fails to do it's job. As the session was ending, he told us he never wanted to see something like this happen again. And if it did, he continued, we needn't return to class because we would be receiving F's for the semester. To conclude, he told us the work we had done was worthless. It was late. "In the real world this doesn't fly," he said."But it does in HERE." With that, he took the stack from his desk and hurled it toward the trash can in the corner. Paper flew like a snowstorm blowing hard across the three rivers. There was silence in the room. He walked back to the desk and sat down. "Get out of here," he told us. "We're done for today."

As it turned out, there was only a partial meltdown at the plant. We were safe, at least for the moment. The misadventure, the near crisis in central Pennsylvania that played out over five days in May of 1979 still haunts us today.

Right now, with each passing day, the walls of nuclear power reactor vessels are becoming more brittle. In recent years, operators in the control rooms of nuclear power stations have been found asleep at the switch. Nuclear waste sits at the reactor sites, among other places, waiting for a central repository at which it can be contained. But that is a story for another day.

The positive legacy of Three Mile Island is that since the incident no new operating license application has been filed.

I just had a shiver go up my spine. There is not a place in the continental United States that you can live where you are safe from a catastrophic failure at a nuclear power facility. An area the size of Pennsylvania would be rendered uninhabitable for thousands of years. Even worse, if it happens tomorrow, or next month or two years from now, George W Bush and his blundering band is who we will have to depend on.

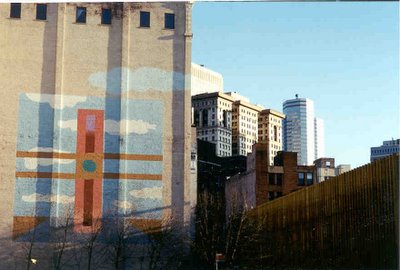

Photography by KILORY_60

Photograph by KILORY_60

Photograph by KILORY_60